Fine Art Photography Checker

Conceptual Intent

Does the photograph express a clear idea, emotion, or question?

Formal Control

Does the photograph show mastery over composition, lighting, and technique?

Presentation Context

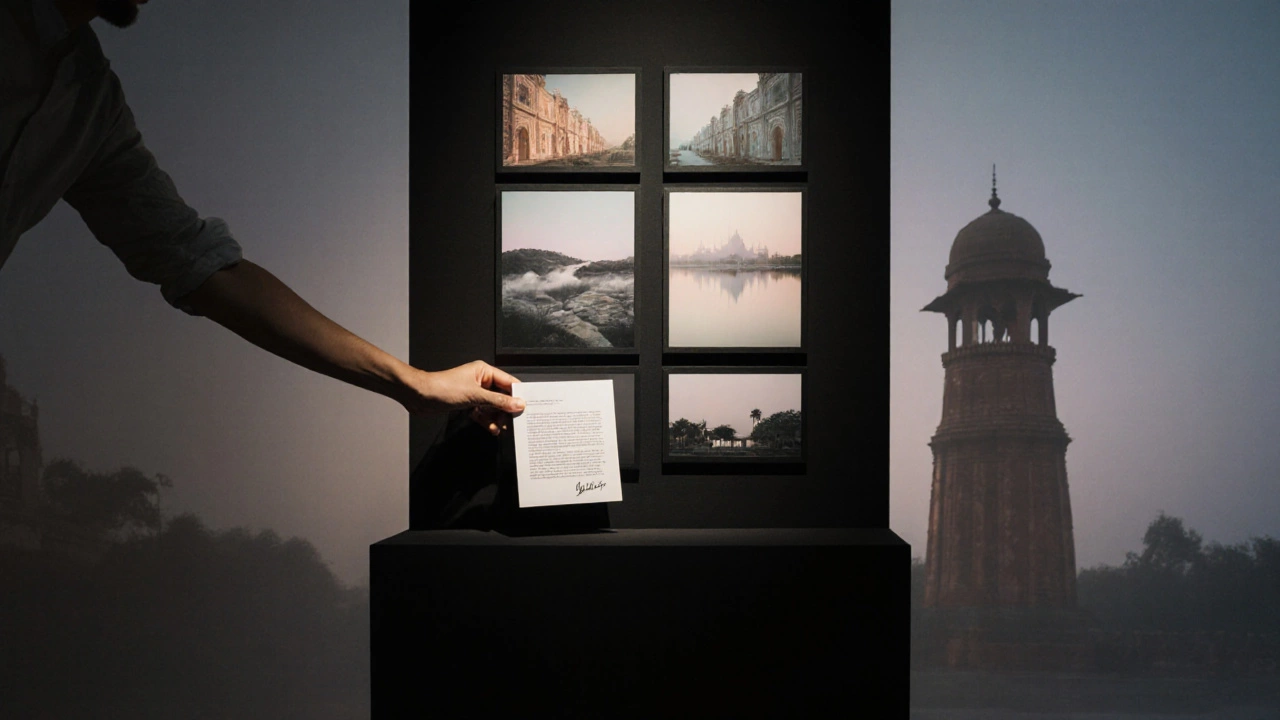

Is the work presented in an art context (gallery, museum, curated exhibition)?

Additional Criteria

Does the work demonstrate originality, technical excellence, and a clear artist statement?

Evaluation Results

Click "Evaluate This Photograph" to see if your image qualifies as fine art photography based on key criteria.

- Clear, high-resolution files (minimum 300 dpi)

- Signed artist statement (150-250 words)

- Proof of edition size and numbering

- Printing details (method, paper type)

- Portfolio of 8-12 cohesive images

- Biography with exhibitions and awards

Quick Takeaways

- Fine art photography is driven by the creator’s vision, not by documentation or sales goals.

- Core criteria include concept, composition, lighting, and intent.

- Recognition often comes from galleries, museums, and curated exhibitions.

- Print quality, edition size, and artist statements add market value.

- Building a fine‑art portfolio requires a clear narrative and consistent branding.

When people talk about fine art photography is a genre where the photographer’s creative vision, intent, and artistic expression drive the image, rather than purely documentary or commercial goals, the focus shifts from “what” was captured to “why” it matters.

What makes a photograph a piece of fine art?

Three pillars hold the definition together:

- Conceptual intent - The photographer starts with an idea, a question, or an emotion they want to explore. The final image is a visual answer.

- Formal control - Mastery over composition, lighting, color, and texture turns a snapshot into a crafted object.

- Presentation context - When the work is shown in a gallery, museum, or curated online platform, it is framed as art rather than a product.

Unlike a wedding photo that records an event, a fine‑art image is judged on its ability to provoke thought, evoke feeling, or re‑contextualise familiar subjects.

Key attributes to evaluate

Here are the most common checkpoints used by curators, collectors, and critics:

- Originality: Does the image offer a fresh perspective or a unique visual language?

- Technical excellence: High‑resolution capture, meticulous post‑processing, and precise print output.

- Conceptual depth: A clear narrative or philosophical underpinning, often explained in an artist statement.

- Edition strategy: Limited‑edition prints signal scarcity and increase collectability.

- Contextual relevance: Alignment with contemporary art movements or historic references.

Fine Art vs Commercial Photography: Core Differences

| Aspect | Fine Art | Commercial |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Express an idea or emotion | Sell a product or service |

| Creative Control | Artist dictates every element | Client briefs dictate most decisions |

| Audience | Collectors, curators, art‑savvy public | Consumers, advertisers, media outlets |

| Distribution | Limited editions, gallery sales | Mass‑print, online ads, editorial |

| Value Metric | Artistic merit, scarcity | Reach, conversion rate |

The table makes it clear that the two worlds share tools-cameras, lighting gear, post‑processing software-but the endgame diverges sharply.

How galleries and museums validate fine art photography

Institutions act as gatekeepers. A photographer’s first encounter with a gallery is a physical or virtual space that curates and sells artwork to the public usually involves a submission portfolio, an artist statement, and often a proof of print quality. Curators look for a cohesive body of work that can stand alongside paintings, sculpture, and other media.

When a museum includes a photographer in its permanent collection, it signals scholarly endorsement. Museums require provenance documentation, consistent printing standards (archival paper, pigment‑based inks), and a clear lineage of ownership.

Both venues provide the narrative context that turns a photograph into fine art: wall text, catalogue essays, and curated shows that tie the image to larger artistic movements.

Print quality and editioning: Turning a digital file into a collectible object

Even the most visionary concept collapses without a physical form that endures. Professional printers use C‑type processes, silver‑gelatin papers, or museum‑grade canvas. The choice of camera is the device-digital or film-that captures the original image, influencing resolution, dynamic range, and colour fidelity matters, but the final print medium is where the work gains permanence.

Limited editions are marked with a number (e.g., 5/50) and signed by the artist. Collectors treat these as “art objects” because scarcity drives value, similar to a painting’s size or medium.

Building a fine‑art photography career: Practical steps

- Define your visual language. Sketch a series of concepts, research art history, and write brief statements that explain each idea.

- Invest in high‑quality equipment. Full‑frame DSLR or medium‑format mirrorless bodies paired with prime lenses give you control over depth of field and tonal range.

- Master lighting. Natural light, studio strobes, or mixed setups should be deliberately shaped to support your concept.

- Create a consistent body of work. Aim for 8‑12 images that speak to each other; variability confuses curators.

- Produce archival prints. Work with printers who use ICC‑profile‑matched papers; order a small test run before final editions.

- Write a compelling artist statement. Keep it under 250 words, focus on motivation, influences, and intended impact.

- Submit to galleries and juried shows. Follow each venue’s guidelines-typically a PDF portfolio, high‑resolution JPGs, and the statement.

- Engage with collectors. Attend art fairs, use social media to showcase behind‑the‑scenes processes, and offer limited‑edition releases.

Success is rarely instant; persistence, self‑evaluation, and networking are as vital as the camera itself.

Case studies: Photographers who cracked the fine‑art code

Case 1 - Ansel Adams (landscape): Adams turned wilderness into myth by mastering the Zone System, a technical method that translates tonal values into print density. His prints still fetch six‑figure sums at auction, proving that precision and concept can combine for lasting value.

Case 2 - Cindy Sherman (conceptual portraiture): Sherman stages herself in dozens of roles, questioning identity and media representation. Her work appears in major museum collections; each edition is limited to maintain rarity.

Case 3 - Alex Webb (color street photography): Webb’s layered compositions capture the frenetic energy of urban life. Though his images often look documentary, he frames them with a painterly eye, earning spots in galleries worldwide.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

- Relying on trends. A photo that mimics a current Instagram style may look popular but rarely survives the museum gate.

- Neglecting the artist statement. Curators need context; without it, even stunning images can be dismissed as “beautiful snapshots.”

- Skipping archival printing. Low‑quality paper fades; a collector will never buy a work that degrades in ten years.

- Over‑producing editions. Unlimited prints dilute scarcity and lower market price.

Checklist for a fine‑art photography submission

- Clear, high‑resolution JPG or TIFF files (minimum 300dpi).

- Signed artist statement (150‑250 words).

- Proof of edition size and numbering. \n

- Details on printing method, paper type, and printer.

- Portfolio of 8‑12 cohesive images.

- Biography with exhibitions, awards, and any museum acquisitions.

Next steps for aspiring fine‑art photographers

If you’re ready to move from hobbyist to artist, start by picking a single concept and creating a small series. Document every step, from lighting set‑up to print proofing. Then draft an artist statement and reach out to a local gallery that shows emerging artists. Treat every rejection as feedback-refine your concept, improve your printing, and try again.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is any photograph automatically fine art if I price it high?

No. Price alone does not confer artistic status. Fine art is defined by concept, control, and presentation. Without a clear artistic intent and curatorial context, a high price is seen as market speculation, not art.

Can digital images qualify as fine‑art photography?

Absolutely. The medium-digital or film-doesn’t determine art status. What matters is the photographer’s vision and the quality of the final printed object. Many contemporary artists use digital workflows and still exhibit in museums.

How many prints should I make for a limited edition?

There’s no hard rule, but 10‑50 prints is common. Smaller editions command higher prices; larger ones make the work more accessible but can reduce exclusivity.

Do I need a gallery contract to sell fine‑art prints?

A contract clarifies commissions, shipping, and resale rights, so it’s highly recommended. Some artists also sell directly online, but galleries provide validation and reach that independent sales often lack.

What role does the artist statement play in a submission?

It gives curators the narrative they need to place your work within an artistic discourse. A concise, thoughtful statement can turn a technically brilliant image into a compelling art piece.