Paris, 1874: a bunch of painters, fed up with the snobby French Academy, hung their work in a dusty studio and called it an exhibition. They didn’t know it, but this rebellion would fling open a door that reshaped art forever. The modern art movement, usually pinpointed to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, didn’t just “start” one day. It brewed out of social uproar, technological changes, and a general sense that the whole world was changing fast. The wild thing? Most of these artists—think Monet, Van Gogh, Picasso—weren’t aiming to start a revolution. They just wanted to paint the world the way they felt it, not the way their teachers told them to. That single, radical shift is what made modern art take off.

Cracks in the Canvas: Why Did Modern Art Appear?

If you step back and look at European painting before the 1800s, it was about drama, religion, and detail—lots and lots of detail. Scenes looked polished, realistic, and almost like photographs (if cameras had been a thing back then). But by the middle of the 19th century, things were shifting. Cities were booming. Factories were popping up. Cameras actually had arrived, making perfect portraits and landscapes suddenly less impressive. People were more interested in what was new, weird, and even shocking. Absolute faith in “tradition” started to look outdated, especially to artists living in bustling cities like Paris, London, Berlin, and New York.

Think about the impact of inventions at the time. Trains let people zip between cities, and suddenly, new places, ideas, and even light itself were being experienced in fresh ways. Painters like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro dragged their easels outdoors—plein air painting—trying to capture what sunlight actually looked like minute to minute. Never mind that the results looked blurry or “unfinished” to critics at the time. Monet’s piece, “Impression, Sunrise,” literally coined the term for the Impressionist movement and got mocked for looking more like a sketch than a "real" painting. Except people started to love seeing the world through these fresh eyes. This wasn’t about snobs in velvet coats deciding what was good; it was about ordinary people feeling something when they looked at art.

Social changes played just as big a part. The old world was falling apart, and after events like the French Revolution and the rise of industrial cities, nobody expected art to stay stuck in the past. “Avant-garde”—meaning the “advance guard” or the ones out ahead—became a buzzword for artists trying to shock, challenge, or even annoy the establishment. Instead of just painting pretty mythological or historical scenes, these artists asked: what if we show normal people, streets, fields, city chaos—or even our own nightmares and daydreams?

You could compare the situation to the rise of punk music in the late 1970s. Both were less about a particular style and more about breaking the rules. In art, it meant suddenly you had noisy, even ugly, experiments right next to old, safe landscapes. Not everyone liked seeing things get upended. In fact, critics in Paris outright called the first Impressionist exhibit a disaster. But the cat was out of the bag. As one famous statistic shows: within thirty years of that first show, over 1,500 artists in Europe were calling themselves Impressionists or something close to it. The ripples went worldwide.

Pivotal Moments and Movements That Ignited Modern Art

Three artists often get credit for jumpstarting the whole shebang: Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, and Paul Cézanne. Each took a risk that broke the mold for future artists. Manet shocked viewers with "Olympia" in 1865, painting a nude woman who stared back at you—no shrinking violet, just a real person. Critics gasped. Cézanne, meanwhile, flattened nature into weird, geometric shapes, creating a strange sense that trees and houses might collapse or twist. Monet, as mentioned, focused on the flickers of light and color in moments that passed by in seconds.

Don’t let anyone tell you it all stopped there. Picasso’s "Les Demoiselles d’Avignon" from 1907 ripped away any trace of realism. He mashed up faces, bodies, and African art influences in a way people had never seen before. Around the same time, artists in Vienna—think Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele—were painting with gold and extreme emotions. Russians like Wassily Kandinsky said, “Why not forget about painting anything you recognize?” and started making wild swirls and blotches that were pure feeling, not objects.

Here’s a rundown of key movements that helped modern art explode:

- Impressionism: Capturing fleeting light, color, and regular life—Monet, Degas, Renoir.

- Post-Impressionism: Pushing further—Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin, mixing color and personal vision.

- Fauvism: Vivid, almost clown-color palettes—Henri Matisse topping the list.

- Cubism: Slicing up shapes and turning scenes into puzzles—Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.

- Expressionism: Letting emotions explode onto the canvas—Edvard Munch’s “The Scream.”

- Abstract Art: Ditching recognizable objects completely—Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian.

- Dada and Surrealism: Absurd, playful, and wild—Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí.

If you’re wondering just how fast things moved, check this out:

| Movement | Years Active | Key Figure |

|---|---|---|

| Impressionism | 1870s–1890s | Claude Monet |

| Post-Impressionism | 1885–1910 | Vincent van Gogh |

| Cubism | 1907–1920s | Pablo Picasso |

| Fauvism | 1905–1908 | Henri Matisse |

| Surrealism | 1920s–1940s | Salvador Dalí |

Notice how each style lasted only a decade or two at most before artists moved on. Unlike the centuries-old Renaissance or Baroque traditions, modern art thrived on change. Nothing stayed trendy for long. People who love the old masters might have found this dizzying, but for the new crowd, it was thrilling.

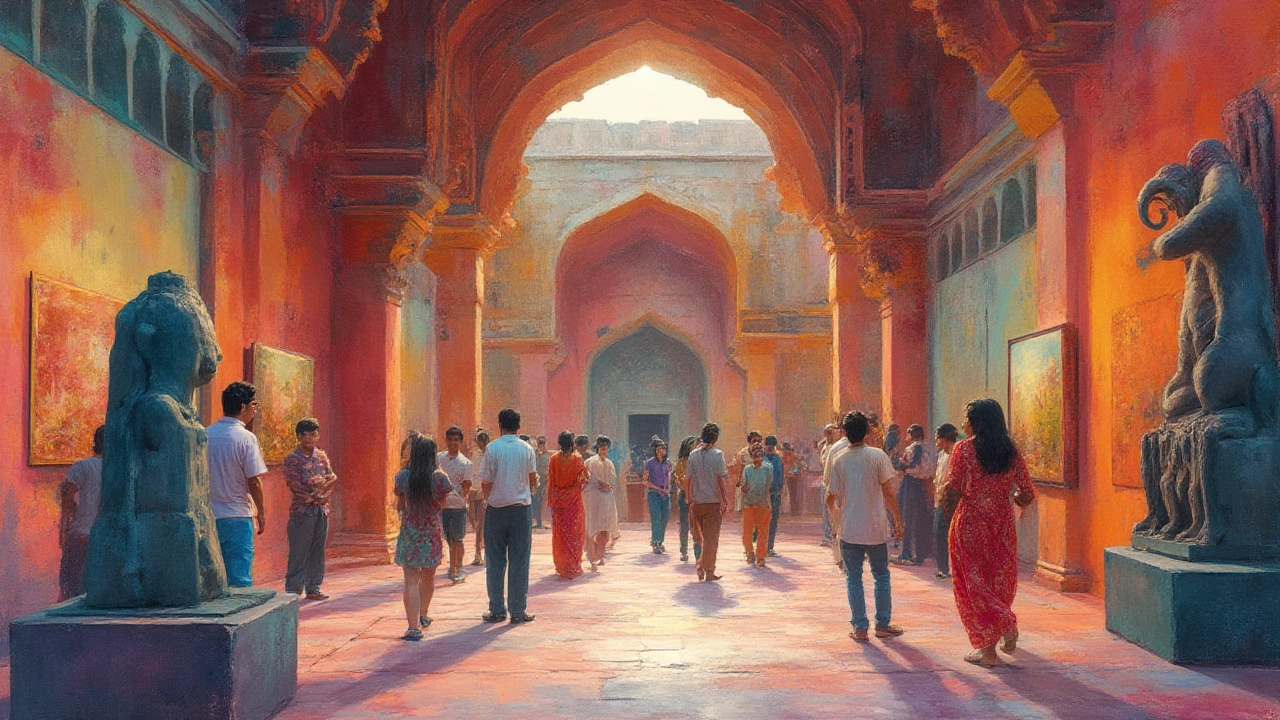

If you’re dipping your toes into modern art, try checking out famous museums—either in person or virtually. The Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Tate Modern in London, and even the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney have floor after floor dedicated to these wild experiments. It’s worth getting up close; seeing the crazy brushstrokes, thick smears of paint, and surprising color choices drives home just how daring these artists were.

Modern Art’s Legacy and Why It Still Matters

Modern art didn’t just upend painting. Its shockwaves reached into sculpture, photography, printmaking, and eventually film and design. Take Marcel Duchamp, who in 1917 plopped a regular urinal in a gallery and titled it “Fountain.” This wasn’t just a joke—it asked people, “What even counts as art?” Suddenly, the idea you could challenge what’s “good” or “beautiful” blew right out the window. Artists could paint with garbage, make collages, snap strange photos, or even just arrange objects.

The push for freedom spread well beyond Europe and the US. Japan saw movements like Gutai in the 1950s, Australia gave rise to wild bush paintings and Indigenous artists mixing tradition with radical new media, like Emily Kame Kngwarreye, whose dot-and-line paintings shook up expectations in the ‘80s and ‘90s. All this comes directly from that first wave of rebellious energy over a century ago. The core spirit remains: be bold, be honest, and find a personal truth—even if it’s not pretty or popular.

Modern art still fires up debates, even in 2025. Is a canvas with nothing but a red stripe “real art”? What about digital pieces or NFTs, the new kids on the block? The questions stay the same as they were a hundred years ago, but the tools and answers keep changing. One fun tip: when looking at modern art, try to see it as the artists did—not as an answer, but as a big, messy experiment. Forget what’s hanging in grandma’s lounge room. Track down a work that makes you go, “What the hell?” That’s usually the best sign you’re seeing the real, rebellious core of modern art.

Want to try making your own? Grab some paints, a sketchbook, or just anything you have lying around. Don’t worry about getting things right. Modern art started with people who broke all the rules, so you don’t need to follow any. See what happens when you mix odd colors or scribble something out of boredom or frustration. That’s how it began—with curiosity, courage, and a refusal to just mimic what came before. The rest, as they say, is still being painted.