People look at a blank canvas with a single brushstroke and ask: modern art lacks skill. It’s not just casual viewers. Even art lovers pause, frown, and wonder if a five-year-old could’ve done it. But here’s the thing-modern art isn’t trying to be what you think it is. It’s not about rendering a perfect face or painting a realistic sunset. It’s about asking different questions. And that’s why the skill looks invisible.

What We’re Missing When We Say ‘Lacks Skill’

We’re trained to measure art by technical precision. A Renaissance portrait with lifelike skin tones, delicate shadows, and perfect perspective? That’s skill. A Jackson Pollock drip painting? It looks messy. But that’s because we’re using the wrong ruler. The skill in modern art isn’t in copying reality-it’s in breaking the rules on purpose. It’s in knowing exactly how far you can push before the viewer stops seeing chaos and starts seeing meaning.

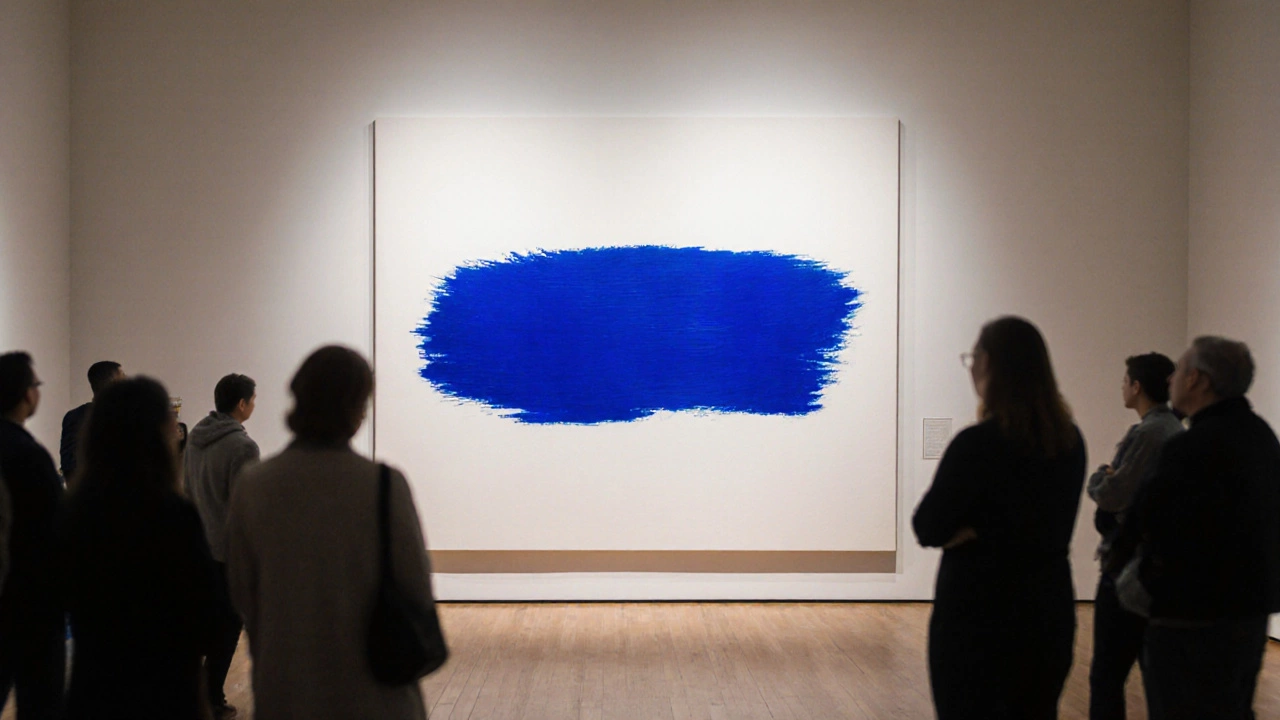

Take Yves Klein’s International Klein Blue. He didn’t just pick a shade of blue. He invented a pigment formula that held its color without losing intensity. He coated entire walls, objects, even human bodies in it. The skill wasn’t in brushwork-it was in material science, in performance, in forcing people to feel the weight of a single color. That’s not easy. It’s harder than painting a perfect apple.

Art Changed When Cameras Took Over Realism

In the 1830s, photography arrived. Suddenly, you didn’t need to spend months painting a detailed landscape to capture it. Cameras did it faster, cheaper, and more accurately. Artists didn’t quit-they got restless. Why paint what a machine could do better? So they turned inward. They asked: What can art do that a camera never can?

That’s when Impressionism exploded. Monet didn’t paint trees with perfect leaves. He painted how light danced on them. Van Gogh didn’t copy the night sky-he painted how it felt to stare at it, dizzy and alive. These weren’t failures of skill. They were revolutions. The brushstroke became emotional. Color became psychological. The artist’s hand became the subject.

By the 1950s, artists like Barnett Newman were painting giant fields of color with razor-straight edges. No texture. No detail. Just pure presence. Critics called it lazy. But Newman spent years testing pigments, canvas tension, and scale to make that single stripe feel monumental. The skill was in restraint. In knowing when to stop.

Modern Art Isn’t About Technique-It’s About Concept

Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain-a porcelain urinal signed ‘R. Mutt’-is often the go-to example of ‘this isn’t art.’ But it wasn’t about the object. It was about the idea: Who decides what counts as art? He forced museums, critics, and the public to confront their own biases. That’s a radical act. And it required deep understanding of art history, institutional power, and human perception. That’s skill. Just not the kind you learn in a life drawing class.

When Ai Weiwei smashed a Han Dynasty vase, he wasn’t destroying history. He was asking: Can something lose its value when we stop believing in its meaning? The skill was in the timing, the symbolism, the political risk. He didn’t need to carve marble. He needed to understand how culture works.

Modern art often feels empty because it’s not trying to fill your eyes. It’s trying to fill your mind. The skill lies in making you uncomfortable enough to think.

Why We Still Judge Modern Art by Old Standards

We grow up seeing art as a trophy of mastery. The more realistic, the better. That’s what museums taught us for centuries. But modern art doesn’t care about trophies. It cares about questions. And we’re still stuck in the old system.

Think about music. If you heard a single sustained note from John Cage’s 4’33”, you might say, ‘That’s not music.’ But the piece isn’t about sound-it’s about silence, attention, and the environment around you. The skill is in framing the moment. Same with modern art.

Most people never learn to read the language of modern art. They’re still trying to translate it into Renaissance terms. That’s like trying to understand a haiku by measuring its syllables against Shakespeare. You’re using the wrong grammar.

Art schools today don’t just teach drawing. They teach semiotics, philosophy, media theory, and social critique. A student might spend a year researching the history of waste before making a sculpture from recycled plastic bottles. That’s not a lack of skill-it’s advanced training.

The Real Skill: Making People Care

The hardest part of modern art isn’t painting a shape. It’s making someone stop scrolling, look longer, and feel something. That’s the real test.

Take Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project at Tate Modern. He filled a giant hall with a fake sun made of lamps and mist. Thousands sat on the floor, staring up, taking selfies, lying down like they were on a beach. Some cried. Others just sat in silence. The piece didn’t need brushstrokes. It needed engineering, light design, psychology, and a deep understanding of how crowds behave.

That’s skill. The kind that can’t be measured in hours of practice. It’s measured in how many people pause, look, and wonder.

Modern art doesn’t lack skill. It redefines it. And that’s why it’s so hard to accept. We’re not used to valuing ideas over execution. But the most powerful art in the last 100 years didn’t come from perfect hands. It came from bold minds.

What You’re Really Seeing

When you look at a blank canvas or a pile of bricks and think, ‘I could do that,’ you’re not seeing the years of research, the failed experiments, the debates with philosophers, the trips to museums, the rejections from galleries. You’re not seeing the artist who spent three months testing how light hits a single metal sheet before deciding it was right.

You’re seeing the result. Not the process. And that’s the trick.

Modern art doesn’t hide its skill. It hides it in plain sight. In the silence between the lines. In the space between the thought and the object. In the moment you realize you’re not looking at a painting-you’re looking at a question.

Maybe the real question isn’t whether modern art lacks skill. Maybe it’s whether we’re still willing to learn how to see.

Is modern art really art if anyone can make it?

Just because something looks simple doesn’t mean it’s easy to create with purpose. A child can smear paint, but an artist uses that smear to challenge centuries of tradition. The difference isn’t in the action-it’s in the context, intention, and understanding behind it. Modern art isn’t about ‘anyone can do it.’ It’s about ‘anyone can be made to think differently.’

Why do museums display things that look like trash?

They’re not displaying trash-they’re displaying ideas. A pile of tires by César Baldaccini isn’t about the tires. It’s about consumer culture, waste, and transformation. Museums act as laboratories for ideas, not just pretty objects. If you walk away thinking about how much we throw away, the artwork did its job.

Do artists even know what they’re doing?

Most do. Many modern artists spend years studying theory, history, and philosophy before they make a single piece. They’re not winging it. They’re building arguments with materials. Some even collaborate with scientists, engineers, or sociologists. What looks random is often the result of deep research.

Why is modern art so expensive if it’s ‘easy’?

It’s expensive because it’s rare, risky, and culturally significant. A single dot by Agnes Martin sold for $15 million-not because it took long to paint, but because it changed how people think about minimalism, spirituality, and silence in art. Value isn’t about labor. It’s about influence.

Should I try to understand modern art, or just enjoy it?

You don’t need to ‘understand’ it like a math problem. But you can let it sit with you. Ask: Why did the artist make this? What does it make me feel? What does it say about the world? You don’t need a degree to feel something. But if you want to know why it matters, a little curiosity goes a long way.